D: You grew up in the Detroit area and were around the same age as other locals like the people who would form The Stooges and MC5, and Klaus Flouride, who would go on to be in the Dead Kennedys. Did you know of or were you aware of any of them?

L: I never met Klaus Flouride, not even in the Dead Kennedys days, and to be honest, was only vaguely aware that he was from Detroit. However, I grew up about a mile away from the MC5 (most of them, anyway), and first saw them in 1965, when they were still a mod/garage type band and hadn’t yet joined up with the hippies and the revolution. The Stooges were from Ann Arbor, which was about 40 miles away, and didn’t form till 1968, which was when I first saw them.

I also saw a fair bit of the MC5 during the later 60s, since both they and I eventually moved to Ann Arbor. However, I didn’t socialize with most of them; I met Iggy only in passing, and while I later spent some time hanging out with Ron Asheton of The Stooges and Michael Davis of the MC5, it was in the late 70s/early 80s when they were playing in Destroy All Monsters.

D: What was your adolescence like? I read that the Screeching Weasel song “High School Psychopath” was written about a young you.

L: I don’t think I’ve ever heard that rumor before. In fact, I’m not even sure I’m familiar with that song (I know The Queers version, because I worked on it with them when they were recording Move Back Home). Anyway, whether or not Screeching Weasel were singing about me, “psychopath” might not be too harsh a description, though “sociopath” might be more accurate. I spent most of my teenage years hanging out with gangs that grew increasingly vicious and more criminally oriented as I got older. One of my last gangs got broken up when pretty much everyone except me was sent to prison. I drank a lot, got in a fair bit of trouble, and would have gotten in a lot more if I’d been caught for some of the stuff I did, like carrying a gun to school with me almost every day when I was 16 and 17. I guess you could look at me in two ways: as a nasty piece of work, or a poor, misguided kid who needed some serious help. Both would probably be true.

D: When and why did you leave Michigan?

L: My story was much like that of Lily Tomlin, who, asked when she left Detroit, responded, “As soon as I realized where I was.” More specifically, I left in early 1968 because the police were after me.

D: Was there a specific moment when you first felt aligned with the punk scene?

L: Depends which punk scene you mean. If you’re talking about the proto-punk scene of the MC5 and The Stooges, early 70s. If you mean ’77 punk, it would be the time I was bopping down Polk Street in San Francisco with a big boom box playing the Ramones and some girl with a fake English accent called me a poser. Two years later that same girl tried to steal my leather jacket at a party, and called me a poser again when I stopped her. No English accent this time, though; it had gone out of style by then.

D: What were some of the shows you saw during the first wave of punk? Were you at the Sex Pistols Winterland show?

L: Yes, I was at the last Sex Pistols show at Winterland in January of 1978. First two shows I remember seeing [in San Francisco] were the Ramones/Dictators at Winterland and the Nuns/Avengers at the Mabuhay, in August and/or September of 1977.

D: I have read a lot of accounts from the 1980s of police violence against the LA punk scene (or the Los Angeles public in general, for that matter). Was this the case in San Francisco or other cities in the Bay Area?

L: Yeah, I didn’t spend a lot of time in LA, and when I was there I never ran into any trouble with the police, but the cops at that time did have a reputation for being very harsh with people in general, not just punks. To be fair, I think the prevailing ethos of the LA punk scene was more obnoxious and confrontational, so they may have brought some of it on themselves, but once again, I wasn’t there enough to have an informed opinion on the matter.

San Francisco and the Bay Area were very different. Hell, the sheriff of San Francisco County used to come to shows at the Mabuhay. As a fan, not as a cop. Most of the time when there was violence, it was an outgrowth of some sort of political demonstration, like when the punks were protesting at the 1984 Democratic Convention and a whole lot of them got arrested and some got roughed up. The SF cops did beat up a roommate of mine pretty badly when they caught him spray painting, but I think that was mainly because they were mad at him for running away and making them chase him. I just heard from him recently, by the way: he’s a very successful psychotherapist now.

D: I think you have a point, just generalizing as an outsider, people in the San Francisco area seem to be presented as more conscious, mellow, and intellectual than those in the LA area. After that recent B.A.R.T. Cop verdict I thought for sure their would be violence and riots, and there wasn't, meanwhile I read there was a riot at a TSOL show in L.A. the other day.

Switching gears, which came first, The Lookouts, Lookout Records, or the Lookout fanzine?

L: Well, it’s a bit of a gray area. My usual answer is Lookout magazine, but if you want to get really technical about it, the first few issues of Lookout (which started in October 1984) had different names, first the Iron Peak Lookout (named after the nearby fire lookout tower atop the nearest mountain) and then Mendocino Mountain Lookout. It didn’t become simply the Lookout (and primarily a punk zine) until summer of 1985, by which time The Lookouts were already in existence, too (I think our first practice was in February of that year). Lookout Records didn’t really get started until 1987.

D: Speaking of zines, do you ever re-read your old MRR columns?

L: Not too often. I don’t even have a lot of them. Occasionally I dig some of them up and contemplate posting them on my blog, but usually end up deciding they’re too retarded or would need too much rewriting or both.

D: In the internet age, do you think the current incarnation of MRR is relevant?

L: As long as there are people who are interested in publishing it and reading it, I’m sure it is. Obviously it doesn’t play the central and crucial role it once did, when it was the single most important media outlet on the punk rock scene, but at the same time, I wonder why you refer to it as “the current incarnation,” since as far as I know it’s been publishing without interruption since 1982 and therefore would seem to have had only one incarnation. I should say that I’m very impressed that it’s managed to keep going as reliably as ever for all these years since Tim Yohannan died, because I honestly didn’t expect it to survive without him. I think it’s a real tribute to his memory and to his organizational skills that people were able to step in and carry on the tradition while barely missing a beat.

D: I guess I'm referring to it as "it's current incarnation" because it's role seems so detached from what it once was, and what it's history has made it out to be. I hadn't read an issue (other than .pdf files of ones from the late 80s/early 90s) until this summer when one of my roommates brought home a bunch of them that they were gonna throw out at the record store he worked at. I found the newer issues to be good reads, but having grown up with the internet and sites like punknews.org or message boards, I didn't see the need to subscribe.

Were you in bands prior to The Lookouts?

L: Not really. It took a couple years and several different members before The Lookouts finally got off the ground, but they were my first real band.

D: Before I ask about some of the more popular bands, when people reflect on the label’s legacy, what bands do you feel get overshadowed?

L: Oh, lots, but a couple of my favorites were Brent’s TV and Nuisance. Brent’s TV were different enough (semi-acoustic, a bit folky) that you might not expect them to have great success with the punk or alternative crowd, but to me Nuisance were in the same league as Nirvana, albeit more original, so I genuinely did expect them to be more successful than they were. On the other hand, Nirvana might not have done that well on Lookout, either, because they appealed to a somewhat different audience. I mean, there was some overlap, but they weren’t really a part of our scene. Maybe Nuisance should have been on Sub Pop instead.

Also, this might sound self-serving, but I kind of feel like The Lookouts got lost in the shuffle, partly because we put out such an awful first record that many people never bothered checking us out again after we got better, and partly because we broke up just before the CD era, so our releases were only on vinyl and cassette and were long out of print by the time Lookout started getting so much attention in the wake of Green Day and Op Ivy’s success.

D: To me the three bands that best represent your time with Lookout are Operation Ivy during the early years, Green Day with the two albums they released, and finally Screeching Weasel, when they released all those classic albums in the early to mid-90s. Could you talk about each of those bands and your relationships with them, from first hearing them, to being their label boss, to them leaving or disbanding?

L: I might put The Queers in there, too, but as for the three you mention: Operation Ivy were the first, with their 7” coming out as one of Lookout’s earliest releases. I already knew Tim/Lint before Op Ivy formed, and the first time I saw them at Gilman, which was late August or early September 1987, I immediately said, “Let’s make a record.” It might have been slightly premature – they’d only been a band for three or four months – but by the time they recorded in November, they were more than ready, and it was nothing but onward and upward from there.

It was a little more than year later when I first saw Green Day, sometime in the fall of 1988, and they were an even newer band than Op Ivy had been, but the same thing happened: I instantly asked them to make a record. This “show” was meant to be a high school party that Tre (who was still in The Lookouts at that time) had set up, but because of bad weather only five kids showed up, yet Green Day (I should say Sweet Children; they didn’t change their name until March of 1989) put one of the best shows I’d ever seen. Their first 7” came out in April of 1989, and while it didn’t catch on quite as fast as Operation Ivy, probably because they were too “poppy” for some of the “punks,” again it was nothing but onward and upward from then on.

Screeching Weasel, I first saw when they came out to California in 1988 to play at Gilman with Operation Ivy. They were staying with Matt and Lint, which was where I first met Ben Weasel, though his reputation had preceded him thanks to his controversial (and hilarious) scene reports in MRR. Even then he had already made a lot of enemies, but most of us at MRR (I was working on the magazine and, I think, living at the MRR house at the time) were fans. I offered to put out his record, too, but he already had set up a deal with a new Chicago label that he was involved with. I guess that didn’t work out too well, and the band broke up. Then for the next year or two, Ben and I talked a lot on the phone. He wanted to start a new band and wanted me to put out the record, but I insisted that he put Screeching Weasel back together and that then I would put out the record. He finally agreed, the new version of Screeching Weasel came out to San Francisco to record My Brain Hurts, and the rest is history.

It’s funny that you refer to me as “their label boss,” because I didn’t do much bossing with any of those bands. All three of them were remarkably self-contained and pretty much did things exactly as they wanted to. That was especially true of Operation Ivy and Green Day; for example, I only dropped in very briefly during the Op Ivy recording sessions, and never even set foot in the studio when Green Day were recording. I had a bit more input with Screeching Weasel, mostly because they, especially Ben, asked for it, but when it came to deciding on songs, arrangements, artwork, all that sort of thing, it was all decided long by them long before they got near the studio. I was there for the entire recording of My Brain Hurts, and was ostensibly the “producer,” but apart from offering a few suggestions, the main one of which, to take a little longer recording, was rejected as being “too expensive,” I was mainly a cheerleader. It was very impressive watching the band work. They had every song totally figured out in advance, and just whipped through the 14 songs on the album and another three they were doing for a compilation in no time flat.

Operation Ivy broke up just as their one and only album was coming out, and who knows what might have happened with them if they’d stuck together; the album still managed to sell in the neighborhood of a million copies even though the band no longer existed. Green Day, well, everybody knows what happened to them: they got bigger and bigger and then they signed to Warner/Reprise and got super-mega-colossal, which for a while had a similar effect on Lookout.

D: To me the three bands that best represent your time with Lookout are Operation Ivy during the early years, Green Day with the two albums they released, and finally Screeching Weasel, when they released all those classic albums in the early to mid-90s. Could you talk about each of those bands and your relationships with them, from first hearing them, to being their label boss, to them leaving or disbanding?

L: I might put The Queers in there, too, but as for the three you mention: Operation Ivy were the first, with their 7” coming out as one of Lookout’s earliest releases. I already knew Tim/Lint before Op Ivy formed, and the first time I saw them at Gilman, which was late August or early September 1987, I immediately said, “Let’s make a record.” It might have been slightly premature – they’d only been a band for three or four months – but by the time they recorded in November, they were more than ready, and it was nothing but onward and upward from there.

It was a little more than year later when I first saw Green Day, sometime in the fall of 1988, and they were an even newer band than Op Ivy had been, but the same thing happened: I instantly asked them to make a record. This “show” was meant to be a high school party that Tre (who was still in The Lookouts at that time) had set up, but because of bad weather only five kids showed up, yet Green Day (I should say Sweet Children; they didn’t change their name until March of 1989) put one of the best shows I’d ever seen. Their first 7” came out in April of 1989, and while it didn’t catch on quite as fast as Operation Ivy, probably because they were too “poppy” for some of the “punks,” again it was nothing but onward and upward from then on.

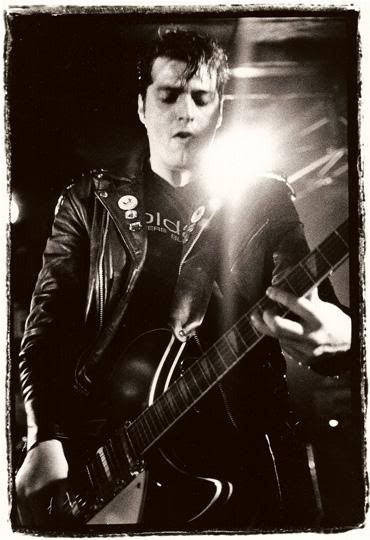

|

| Larry backed by Tre Cool, while in The Lookouts |

It’s funny that you refer to me as “their label boss,” because I didn’t do much bossing with any of those bands. All three of them were remarkably self-contained and pretty much did things exactly as they wanted to. That was especially true of Operation Ivy and Green Day; for example, I only dropped in very briefly during the Op Ivy recording sessions, and never even set foot in the studio when Green Day were recording. I had a bit more input with Screeching Weasel, mostly because they, especially Ben, asked for it, but when it came to deciding on songs, arrangements, artwork, all that sort of thing, it was all decided long by them long before they got near the studio. I was there for the entire recording of My Brain Hurts, and was ostensibly the “producer,” but apart from offering a few suggestions, the main one of which, to take a little longer recording, was rejected as being “too expensive,” I was mainly a cheerleader. It was very impressive watching the band work. They had every song totally figured out in advance, and just whipped through the 14 songs on the album and another three they were doing for a compilation in no time flat.

Operation Ivy broke up just as their one and only album was coming out, and who knows what might have happened with them if they’d stuck together; the album still managed to sell in the neighborhood of a million copies even though the band no longer existed. Green Day, well, everybody knows what happened to them: they got bigger and bigger and then they signed to Warner/Reprise and got super-mega-colossal, which for a while had a similar effect on Lookout.

The story of Screeching Weasel didn’t turn out so happily; while they never reached the levels of Op Ivy or Green Day in terms of fame and sales, they were doing very, very well, but the better they did, the more convinced Ben became that they should be doing even better and that somehow Lookout was standing in the way of that success. Things got worse, much worse, when he became convinced that not only were we doing a poor job of marketing his band, but also that we were somehow cheating him out of part of his money. That in turn degenerated into name-calling, accusations, and a lawsuit, and the band left the label on less than the best of terms, a process that has now been repeated with several other labels. It’s always been my contention that if Ben had devoted even half the energy to writing and performing that he did to fighting and stressing over money, he would have been far more successful, but at least it seems in recent years that he’s finally found a formula for playing shows and making money on his own terms, so perhaps all’s well that ends well?

D: In the years following Operation Ivy, Rancid put out their first EP on Lookout. Was releasing their full lengths ever discussed?

L: It was not discussed per se, which was probably my fault; in those days, it was generally assumed that if you put out a 7” on Lookout and it did reasonably well, you could expect to put out your albums there as well. We rarely dropped bands, and if we did, it was usually for obnoxious or dishonest behavior, not for blatantly commercial reasons.

However, what I wasn’t aware of was that Rancid wanted to be courted and wooed, which Brett Gurewitz had been doing, and which I hadn’t. To be fair, Brett and Tim had also struck up a friendship that wasn’t purely related to the record business, and also to be fair, I wasn’t originally as big a fan of Rancid as I would become later, so it’s understandable that going with Epitaph seemed like a logical progression to them. I was a bit upset at the time, which I didn’t have a right to be, since, as I said, I hadn’t actively pursued keeping them on the label. But again, all’s well that ends well! And I should add that Rancid have had a very long, productive and happy relationship with Epitaph.

D: You produced some of The Queers and Screeching Weasel releases that Lookout did. How would you rate yourself as a producer, and is that role something you’d ever consider doing again?

L: As I already mentioned, my role as Screeching Weasel’s “producer” was minimal, especially on My Brain Hurts. I actually had more input into Anthem For A New Tomorrow when Ben and I went into Art of Ears to remix it (I wasn’t there for the original recording sessions). And it’s also worth noting that I don’t know how to run a board (i.e., engineer); all my production work has been in the theoretical realm, where I give suggestions on how to get the best sound or what harmonies might work well on the choruses, or in some cases, restructuring the song in one way or another. In any case, I would still be dependent on having a good engineer capable of translating my ideas into tangible recordings. Luckily, I had the opportunity to work with some great ones like Kevin Army, Andy Ernst and Mass Giorgini.

I think the production job I’m proudest of would be The Queers Surf Goddess EP, which I worked on collaboratively with The Queers themselves and Mass Giorgini at Sonic Iguana. I also did the first EP by the Invalids, which was hastily done and sounds a lot like My Brain Hurts in terms of both its faults and virtues, but was what I’m pretty sure the band wanted, and an album by the band Scherzo, the latter being slightly more emo (early 90s version, not the modern one) than I was used to working with. It didn’t get heard by a lot of people, but I thought it turned out pretty well. In answer to your question about how I would rate myself as a producer, I’d say that I had and still have a lot to learn, but that I seemed to have a certain natural ability at it. Would I try it again? Yes, I think so, but only with bands that I was especially fond of and only with certain engineers. And by certain, I probably mean Mass Giorgini.

D: Were you aware of Howard Stern talking about seeing and meeting Pansy Division on his radio show? It was from when they did that first big tour with Green Day, and Stern mentioned that he wanted to have Pansy Division come on the show. Was there any attempt at the label to get them on as guests?

L: That story sounds vaguely familiar, but I was never a Stern fan or listener, so no, I wasn’t really aware of it, and I definitely didn’t make any effort to get Pansy Division onto his show. If anything like that did happen, it would have been after I left the label. Some people might say that one of my weaknesses as a label head was that I lacked the initiative or ability to help bands break through into mainstream channels of this sort, and those people might have a point. On the other hand, I always felt that one of the distinguishing characteristics of Lookout was that we were able to get bands heard and sell a lot of records without having to play the promotional games that most labels do.

D: Something that I noticed about Green Day is that they would originally have independent label punk bands go on tour with them, like Pansy Division, the Riverdales, and the Smoking Popes. Now, when it seems like they could have even more sway over who they want opening for them, it’s usually another major label rock band. Is that a reflection of their own changing tastes, something the label orchestrates, or what?

L: I actually asked one of their managers about this not too long ago, because I was curious myself, since I know that the guys in the band still like many of the same small, independent bands that I do. And the explanation I was given makes sense, though it’s not what I would have expected: it seems that in order to tour at the level that Green Day does, even as an opening act, a band has to have either the kind of label support or money of their own that most small, indie bands just don’t have. The reason is that it’s actually quite expensive to tour at that level, and even though the opening acts are paid what would seem like a lot of money to most of us, it’s still not always enough to cover all the costs, especially when the tour is moving rapidly over a great deal of ground. Or, for example, when you need to keep enough merch in stock to sell at places like Madison Square Garden night after night.

Nobody said anything to me about this, but I also couldn’t help wondering if it had something to do with the way that some indie bands just can’t handle the rigors of a big tour, like, for example, when the Riverdales suddenly dropped off the Green Day European tour and left them scrambling for another opener. Of course there was a reason the Riverdales had to do that – Ben was suffering some serious health-related issues that he’s talked about elsewhere – but that doesn’t help Green Day or their management when they need to make sure there will be an opening band for the next show. The bands that open for Green Day nowadays tend to be well-established enough that you know what you’re getting, even if it’s not always exactly what you want. And – though this is also pure speculation on my part – I imagine there’s a bit of politics involved, too, where opening acts might be represented by the same label or management team. At the same time, I wouldn’t be at all surprised if on some future tour, Green Day changes things up by bringing along some totally unknown new indie band. But I’m not part of the team that makes those decisions, so again, I’m just guessing.

D: I remember reading something about how bands that are huge now, like The Offspring and AFI, were trying to get on Lookout in their early years. Is this true, and do you still have any of the demo tapes that bands sent you from back in the day?

L: I don’t remember The Offspring trying to get on Lookout, though there was some talk about it around the time Can Of Pork compilation was being put together. I think Chris Appelgren was talking to one of The Offspring guys about getting a track for that comp, and he (Chris) asked me if I thought maybe we should put out the next Offspring album. I said I’d be willing to do it if that’s what the band wanted, and there might have been a little more talk about it, but nothing came of it.

AFI, on the other hand definitely wanted to be on Lookout. Andy Ernst, who had recorded the tape that would become their first album, gave me a copy, told me he thought it was really good, and asked me to give AFI a chance. I listened to it and decided I’d be willing to put the record out, but when I talked to the other people at Lookout, nobody else wanted to do it. Being the boss and main owner, I could have insisted that we do it anyway, and I probably should have, but this was getting toward the time where I was beginning to lose interest in the way the label was going, and I just didn’t push hard enough for it. No, I didn’t save anything in the way of demo tapes. I’m not much of a collector.

D: Why did you sell your share in Lookout, and why then move to London?

L: First, and I always have to explain this, and most people don’t seem to get it anyway, I didn’t “sell” my share of Lookout. The only money that I took when I left Lookout was my share of the profits that the label had made up until that time. In other words, money that I had already earned, but which I left in the Lookout bank account so that the label would have operating capital. When you sell a business, what you’re selling is basically a) the rights to whatever property it owns, including intellectual property like, for instance, master recordings; and b) what’s called “good will” and/or future prospects, i.e., the reputation that the company has built up and the likelihood that it will continue to make money in the future. I didn’t get any money for either of those things, just, as I said, withdrew my share of the earnings that the label had already accumulated.

If I had actually “sold” the label, I would have walked away with 10 or 20 million dollars, but that would have meant selling it to a major label the way that Sup Pop was. Maybe I’d been reading MRR too long, but I actually believed Lookout was a community resource that needed to continue to belong to the community, and so I was willing to turn it over to people who I thought would continue to run it the same way I had been running it. This turned out to be a big mistake, not so much because I didn’t get the kind of money I could have (though that would have nice), but because the people who took over Lookout ran it into the ground. As I noted earlier, MRR successfully made the transition from its first owner into a community-run magazine, but maybe the difference between MRR and Lookout was that there weren’t millions of dollars involved.

As for why I left, well, I had been feeling burnt out for a couple years already, and I began to lose – or, more accurately – give up control of too much of the label to other people that worked there. The understandable result was that they started running things the way they thought they should be run, which turned out to be quite different from how I thought they should be. But instead of staying there and fighting to reassert my own sense of direction, I started plotting my escape. The final straw came when the whole lawsuit thing blew up with Screeching Weasel and it turned out that one of my partners wanted to take the Weasel side instead of sticking to our guns. At that point, Lookout as it then existed was coming apart no matter what; it was merely a question of which partners would be going and which would be staying. I turned out to be one of those that went.

D: What was the punk scene like in the UK during the late 90s/early 2000s?

L: There were still the faded remnants of old bands from the 70s and 80s playing revival shows and whatnot, but as far as the bands I knew and hung out with, it was very tiny and obscure. There’d be a show once every month or two, and most of the time we’d be excited if more than 20 or 30 people turned up. Not that much different from what was going on with the New York pop-punk bands that were just starting up around that time.

D: When you moved to New York, were you aware of what was going on there in terms of bands like The Ergs! or The Steinways? Were they even around when you first moved there?

L: Yes, I was very aware of what was going on there, and I think it even played a part in my decision to move to New York. I first started seeing The Steinways and The Unlovables and Dirt Bike Annie, and also a few of the out-of-town bands, like The Copyrights, before I moved there. I was very excited about the energy that was kicking up around them.

D: How would you compare the scene you’re involved with now to the one you were involved with at Lookout?

L: Well, it seems to have lost a little of its steam. When I first got to New York (I’d been visiting regularly for several years already), it looked as though everything was about to kick off, and in many ways it reminded me of the early days at Gilman, say around 1987 or so. The only difference was that we didn’t have a Gilman, but to a certain extent I felt that lack was made up for by something that the East Bay scene didn’t have: instant connectivity with like-minded people all over the world via institutions like the Pop Punk Message Board. Just as bands had been formed, shows had been set up, relationships entered into and broken up inside and on the sidewalks in front of Gilman, similar things were happening on the PPMB, culminating in the first couple of Insubordination Fests in Baltimore, which were as much like the old Gilman Street days as anything I had experienced since.

However, in the last couple years, bands have been breaking up faster than they’ve been forming, many people have grown disillusioned and/or succumbed to early-onset middle age (i.e., reached their 30s), and a whole bunch of other, more commercially-oriented fests have sprung up that, while they feature many of the same bands that play at Insub, lack much of the spirit. So I’m feeling slightly discouraged, but only slightly, because heaven knows I’ve been around long enough to be aware that things come and go, and that if we’re in a lull now, there’ll be another time when the excitement will come rushing back. And also, to be fair, even now there are probably other places in America or not even in America at all where great stuff is happening and I just haven’t found about it yet. That’s the way it’s always been, and I don’t see any reason why it shouldn’t continue to be.

D: I feel like here in New England a nice little niche has been made of all these kids in their teens and 20s who live in cities outside of Boston, and are in bands, punkhouses, labels, zines, etc. putting out shows and albums of quality that didn't really exist a few years ago. I was also under the impression that a similar thing was sort of in swing out in the Midwest around Illinois/Indiana/Ohio.

If you had continued running a label, what bands would you have signed between moving back to America and now?

L: Let’s amend that to “What bands would I have tried to sign?” Even in Lookout’s heyday, not every band wanted to be on our label. For example, it took me years and several albums before I was finally able to land The Mr. T Experience. But assuming they’d want to work with me, here are some of the bands that would have been on Livermore Records: The Steinways, The Unlovables, The Ergs!, The Max Levine Ensemble, Delay, The Copyrights, Dear Landlord, The Leftovers, The Dopamines, Be My Doppelganger. I’m sure I’m leaving a bunch of great bands out, but those are the first that come to mind.

D: Would you ever start up a new record label?

L: Probably not. I might be willing to work A&R with an existing label.

D: What current labels are you a fan of?

L: Probably a lot of the ones currently working with the bands I named above. Obviously labels are not quite as crucial as they once were, at least not to me, because pretty much all my music now comes in digital download form. But I have to pay my respect to, for example, Whoa Oh Records, who kept things alive back earlier in the 2000s when it seemed like almost nobody cared, and It’s Alive Records out in California seems to be doing great stuff. Also, a shout-out is in order to my friend Joe Steinhardt’s Don Giovanni Records, which seems like one of the best-run labels around these days, even though, to be perfectly honest, I’m not a huge fan of all the bands they feature.

D: Do you know anything about Lookout’s current state? Will they ever release another album or are they strictly a back catalog?

L: I know they owe a lot of money to a lot of people and don’t seem to be making any progress – or maybe even any attempt – to pay it back. Until they do, it’s hard to imagine them starting to release new records again. It seems like if they did, all their creditors would immediately go after them for a share of the proceeds.

D: You recently did some shows with your old band, the Potatomen. Do you still write songs, and would you record new material with them or other projects?

L: Just the one show so far, though I’d like to do a few more. I really enjoyed it, and it seemed like the crowd did, too. As for writing new songs, well, believe it or not, I’ve been working on the same handful of songs that are almost but not quite finished since the Potatomen stopped playing regularly at the end of the 90s. Seriously; some of them are only missing a few lines out of the lyrics, and I’ve been kicking them around in my head for 10 years or more. However, on the plus side, I’ve lately been playing a lot more guitar and I’ve filled in a few of the blanks. I actually think most of the incomplete songs will be finished this spring and I can finally start on some new ones. Also, we played one song (“Toytown”) at our New York show that had never been released before, and we’ve got a couple others that have not only never been released but have never been played live, though we did demos of them. As soon as someone offers us a show, preferably on the West Coast, especially at Gilman, we’ll be there.

D: As one of the seemingly few people in the their 60s still going to shows, how many people within the punk scene who are now in their teens, 20s, or 30s do you think will stay involved as they reach middle age and beyond?

L: That does seem a little weird when you put it that way, “in their 60s,” but yeah, it’s true. You know, I don’t think it’s fair to measure people’s involvement by a single standard. For example, one reason I’m free to go to a lot of shows, even when it involves traveling some distance, is that I never married or had a family. Obviously things would be different if I had a wife and/or kids waiting at home for me, or if I had some sort of job where I had to be there every day for 50 weeks out of the year. The fact that for the majority of people, that’s what reality looks like doesn’t mean they’ve necessarily lost interest in punk rock music or the punk rock scene, it just means that new priorities have developed in their lives. I don’t think anyone would seriously suggest that a man or woman of any age should neglect their family responsibilities or their personal lives in order to maintain a presence on some nebulous sort of “scene.”

At the same time, I definitely miss seeing many of the people who are no longer able to come out to shows on weeknights or have to visit the in-laws or take the kids to their school play on weekends, but hey, life goes on. Maybe they’ll be back when the kids are grown up, maybe I won’t be around anymore by the time they do. Being part of “the scene” is not like joining the army or a religious cult; it’s something you do because it brings satisfaction and excitement into your life. Most people, given the normal course of events, will eventually find other, non-music-related things that will bring similar or even greater satisfaction and excitement into their lives. But if and when the music is outstanding enough, I expect they’ll still be around. It’s important to remember that they don’t owe their lives to music or “the scene” any more than music or the scene owes any responsibility to them.

D: Something that I’ve noticed about you is that you champion having a sober lifestyle. In some of your writings you describe your earlier lifestyle as seemingly one of heavy psychedelic use, like the piece about going to the original Woodstock Festival. And in Ben Weasel's book, to me he made you out to be a pothead. If it’s not too personal, I was wondering if you could talk about your sobriety and what brought it on.

L: A couple of corrections: first off, I don’t “champion” any sort of lifestyle. Second, I’d like to think of myself as having a life, not a style.

It’s true that I do talk about my experiences with drugs and alcohol, and about the fact that I no longer use either, but not because I’m promoting some kind of program of abstinence for others. My only reasons for talking about this are a) people often ask me questions about my life and seem genuinely curious about it; and b) there’s always the possibility that some of my experiences will be useful to someone who is going through some of the same problems I did.

That being said, I did use a lot of drugs when I was younger, and not just psychedelics or pot, either. It’s worth noting, though, that by the time Ben Weasel met me, I had long since given up psychedelics and all but given up pot. If indeed he was making me out to be a pothead in his book, I’d have to guess it was because he didn’t have that much firsthand experience with real potheads and just assumed that marijuana was the explanation for my seeming a little unusual to him (trust me, there are a lot of reasons why that would be, and one of them was simply that even normal Californians seemed a little weird to people who grew up in the Midwest, and I was definitely not a normal Californian).

In my own case – and this is just speaking for me, not for anyone else – the drugs kind of wore out their welcome on their own, and eventually they were messing up my life more than they were enhancing it, so I gradually quit them – though not without doing a lot of damage first. But with booze it was different: I started out drinking heavily when I was a teenager, tapered off a bit when I discovered drugs, then returned to drinking, and even though by the time I was in my 20s I realized there was nothing particularly cool or desirable about alcohol, I kept on drinking, long after I could see that it was doing serious damage to me.

So I didn’t quit drinking because of some moral crusade or because I thought it was what people “should” do, but because I had to. It was literally killing me. I’m pretty sure that I wouldn’t be alive today if I hadn’t stopped drinking when I did (2001). Now the thing is that among my friends, there are almost certainly people who are having the kinds of problems with alcohol that I was having. But at the same time, there are many people who drink, maybe even get drunk once in a while, but don’t have those problems. Drinking is just something they do now and then, that they can take or leave whenever they want.

The trouble is that I have no way of knowing for sure which is which, which friend desperately needs to stop drinking or else will die, and which friend can go on drinking the rest of his or her life without anything especially bad ever happening.

So I’m in no position to preach or to tell people what they should do. If they want my advice, they can ask for it. Otherwise, I’m just talking about my own experience, strength and hope, and they’re welcome to take from it anything they find useful and to ignore the rest. As I’ve said elsewhere, my life is great now and I’m happy to be a non-drinking, non-drugging writer, musician and occasional punk rocker. I don’t advocate any of that as a life or a lifestyle for anyone else, but it works for me.

D: In the years following Operation Ivy, Rancid put out their first EP on Lookout. Was releasing their full lengths ever discussed?

L: It was not discussed per se, which was probably my fault; in those days, it was generally assumed that if you put out a 7” on Lookout and it did reasonably well, you could expect to put out your albums there as well. We rarely dropped bands, and if we did, it was usually for obnoxious or dishonest behavior, not for blatantly commercial reasons.

However, what I wasn’t aware of was that Rancid wanted to be courted and wooed, which Brett Gurewitz had been doing, and which I hadn’t. To be fair, Brett and Tim had also struck up a friendship that wasn’t purely related to the record business, and also to be fair, I wasn’t originally as big a fan of Rancid as I would become later, so it’s understandable that going with Epitaph seemed like a logical progression to them. I was a bit upset at the time, which I didn’t have a right to be, since, as I said, I hadn’t actively pursued keeping them on the label. But again, all’s well that ends well! And I should add that Rancid have had a very long, productive and happy relationship with Epitaph.

D: You produced some of The Queers and Screeching Weasel releases that Lookout did. How would you rate yourself as a producer, and is that role something you’d ever consider doing again?

L: As I already mentioned, my role as Screeching Weasel’s “producer” was minimal, especially on My Brain Hurts. I actually had more input into Anthem For A New Tomorrow when Ben and I went into Art of Ears to remix it (I wasn’t there for the original recording sessions). And it’s also worth noting that I don’t know how to run a board (i.e., engineer); all my production work has been in the theoretical realm, where I give suggestions on how to get the best sound or what harmonies might work well on the choruses, or in some cases, restructuring the song in one way or another. In any case, I would still be dependent on having a good engineer capable of translating my ideas into tangible recordings. Luckily, I had the opportunity to work with some great ones like Kevin Army, Andy Ernst and Mass Giorgini.

I think the production job I’m proudest of would be The Queers Surf Goddess EP, which I worked on collaboratively with The Queers themselves and Mass Giorgini at Sonic Iguana. I also did the first EP by the Invalids, which was hastily done and sounds a lot like My Brain Hurts in terms of both its faults and virtues, but was what I’m pretty sure the band wanted, and an album by the band Scherzo, the latter being slightly more emo (early 90s version, not the modern one) than I was used to working with. It didn’t get heard by a lot of people, but I thought it turned out pretty well. In answer to your question about how I would rate myself as a producer, I’d say that I had and still have a lot to learn, but that I seemed to have a certain natural ability at it. Would I try it again? Yes, I think so, but only with bands that I was especially fond of and only with certain engineers. And by certain, I probably mean Mass Giorgini.

D: Were you aware of Howard Stern talking about seeing and meeting Pansy Division on his radio show? It was from when they did that first big tour with Green Day, and Stern mentioned that he wanted to have Pansy Division come on the show. Was there any attempt at the label to get them on as guests?

L: That story sounds vaguely familiar, but I was never a Stern fan or listener, so no, I wasn’t really aware of it, and I definitely didn’t make any effort to get Pansy Division onto his show. If anything like that did happen, it would have been after I left the label. Some people might say that one of my weaknesses as a label head was that I lacked the initiative or ability to help bands break through into mainstream channels of this sort, and those people might have a point. On the other hand, I always felt that one of the distinguishing characteristics of Lookout was that we were able to get bands heard and sell a lot of records without having to play the promotional games that most labels do.

D: Something that I noticed about Green Day is that they would originally have independent label punk bands go on tour with them, like Pansy Division, the Riverdales, and the Smoking Popes. Now, when it seems like they could have even more sway over who they want opening for them, it’s usually another major label rock band. Is that a reflection of their own changing tastes, something the label orchestrates, or what?

L: I actually asked one of their managers about this not too long ago, because I was curious myself, since I know that the guys in the band still like many of the same small, independent bands that I do. And the explanation I was given makes sense, though it’s not what I would have expected: it seems that in order to tour at the level that Green Day does, even as an opening act, a band has to have either the kind of label support or money of their own that most small, indie bands just don’t have. The reason is that it’s actually quite expensive to tour at that level, and even though the opening acts are paid what would seem like a lot of money to most of us, it’s still not always enough to cover all the costs, especially when the tour is moving rapidly over a great deal of ground. Or, for example, when you need to keep enough merch in stock to sell at places like Madison Square Garden night after night.

Nobody said anything to me about this, but I also couldn’t help wondering if it had something to do with the way that some indie bands just can’t handle the rigors of a big tour, like, for example, when the Riverdales suddenly dropped off the Green Day European tour and left them scrambling for another opener. Of course there was a reason the Riverdales had to do that – Ben was suffering some serious health-related issues that he’s talked about elsewhere – but that doesn’t help Green Day or their management when they need to make sure there will be an opening band for the next show. The bands that open for Green Day nowadays tend to be well-established enough that you know what you’re getting, even if it’s not always exactly what you want. And – though this is also pure speculation on my part – I imagine there’s a bit of politics involved, too, where opening acts might be represented by the same label or management team. At the same time, I wouldn’t be at all surprised if on some future tour, Green Day changes things up by bringing along some totally unknown new indie band. But I’m not part of the team that makes those decisions, so again, I’m just guessing.

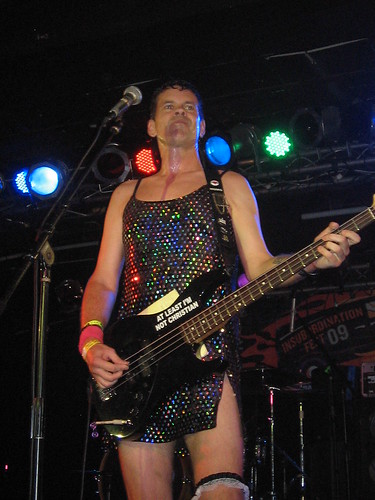

|

| From l-r: Ben Weasel, Jody Sarcastic, Larry Livermore |

L: I don’t remember The Offspring trying to get on Lookout, though there was some talk about it around the time Can Of Pork compilation was being put together. I think Chris Appelgren was talking to one of The Offspring guys about getting a track for that comp, and he (Chris) asked me if I thought maybe we should put out the next Offspring album. I said I’d be willing to do it if that’s what the band wanted, and there might have been a little more talk about it, but nothing came of it.

AFI, on the other hand definitely wanted to be on Lookout. Andy Ernst, who had recorded the tape that would become their first album, gave me a copy, told me he thought it was really good, and asked me to give AFI a chance. I listened to it and decided I’d be willing to put the record out, but when I talked to the other people at Lookout, nobody else wanted to do it. Being the boss and main owner, I could have insisted that we do it anyway, and I probably should have, but this was getting toward the time where I was beginning to lose interest in the way the label was going, and I just didn’t push hard enough for it. No, I didn’t save anything in the way of demo tapes. I’m not much of a collector.

D: Why did you sell your share in Lookout, and why then move to London?

L: First, and I always have to explain this, and most people don’t seem to get it anyway, I didn’t “sell” my share of Lookout. The only money that I took when I left Lookout was my share of the profits that the label had made up until that time. In other words, money that I had already earned, but which I left in the Lookout bank account so that the label would have operating capital. When you sell a business, what you’re selling is basically a) the rights to whatever property it owns, including intellectual property like, for instance, master recordings; and b) what’s called “good will” and/or future prospects, i.e., the reputation that the company has built up and the likelihood that it will continue to make money in the future. I didn’t get any money for either of those things, just, as I said, withdrew my share of the earnings that the label had already accumulated.

If I had actually “sold” the label, I would have walked away with 10 or 20 million dollars, but that would have meant selling it to a major label the way that Sup Pop was. Maybe I’d been reading MRR too long, but I actually believed Lookout was a community resource that needed to continue to belong to the community, and so I was willing to turn it over to people who I thought would continue to run it the same way I had been running it. This turned out to be a big mistake, not so much because I didn’t get the kind of money I could have (though that would have nice), but because the people who took over Lookout ran it into the ground. As I noted earlier, MRR successfully made the transition from its first owner into a community-run magazine, but maybe the difference between MRR and Lookout was that there weren’t millions of dollars involved.

As for why I left, well, I had been feeling burnt out for a couple years already, and I began to lose – or, more accurately – give up control of too much of the label to other people that worked there. The understandable result was that they started running things the way they thought they should be run, which turned out to be quite different from how I thought they should be. But instead of staying there and fighting to reassert my own sense of direction, I started plotting my escape. The final straw came when the whole lawsuit thing blew up with Screeching Weasel and it turned out that one of my partners wanted to take the Weasel side instead of sticking to our guns. At that point, Lookout as it then existed was coming apart no matter what; it was merely a question of which partners would be going and which would be staying. I turned out to be one of those that went.

D: What was the punk scene like in the UK during the late 90s/early 2000s?

L: There were still the faded remnants of old bands from the 70s and 80s playing revival shows and whatnot, but as far as the bands I knew and hung out with, it was very tiny and obscure. There’d be a show once every month or two, and most of the time we’d be excited if more than 20 or 30 people turned up. Not that much different from what was going on with the New York pop-punk bands that were just starting up around that time.

D: When you moved to New York, were you aware of what was going on there in terms of bands like The Ergs! or The Steinways? Were they even around when you first moved there?

L: Yes, I was very aware of what was going on there, and I think it even played a part in my decision to move to New York. I first started seeing The Steinways and The Unlovables and Dirt Bike Annie, and also a few of the out-of-town bands, like The Copyrights, before I moved there. I was very excited about the energy that was kicking up around them.

D: How would you compare the scene you’re involved with now to the one you were involved with at Lookout?

L: Well, it seems to have lost a little of its steam. When I first got to New York (I’d been visiting regularly for several years already), it looked as though everything was about to kick off, and in many ways it reminded me of the early days at Gilman, say around 1987 or so. The only difference was that we didn’t have a Gilman, but to a certain extent I felt that lack was made up for by something that the East Bay scene didn’t have: instant connectivity with like-minded people all over the world via institutions like the Pop Punk Message Board. Just as bands had been formed, shows had been set up, relationships entered into and broken up inside and on the sidewalks in front of Gilman, similar things were happening on the PPMB, culminating in the first couple of Insubordination Fests in Baltimore, which were as much like the old Gilman Street days as anything I had experienced since.

However, in the last couple years, bands have been breaking up faster than they’ve been forming, many people have grown disillusioned and/or succumbed to early-onset middle age (i.e., reached their 30s), and a whole bunch of other, more commercially-oriented fests have sprung up that, while they feature many of the same bands that play at Insub, lack much of the spirit. So I’m feeling slightly discouraged, but only slightly, because heaven knows I’ve been around long enough to be aware that things come and go, and that if we’re in a lull now, there’ll be another time when the excitement will come rushing back. And also, to be fair, even now there are probably other places in America or not even in America at all where great stuff is happening and I just haven’t found about it yet. That’s the way it’s always been, and I don’t see any reason why it shouldn’t continue to be.

D: I feel like here in New England a nice little niche has been made of all these kids in their teens and 20s who live in cities outside of Boston, and are in bands, punkhouses, labels, zines, etc. putting out shows and albums of quality that didn't really exist a few years ago. I was also under the impression that a similar thing was sort of in swing out in the Midwest around Illinois/Indiana/Ohio.

If you had continued running a label, what bands would you have signed between moving back to America and now?

L: Let’s amend that to “What bands would I have tried to sign?” Even in Lookout’s heyday, not every band wanted to be on our label. For example, it took me years and several albums before I was finally able to land The Mr. T Experience. But assuming they’d want to work with me, here are some of the bands that would have been on Livermore Records: The Steinways, The Unlovables, The Ergs!, The Max Levine Ensemble, Delay, The Copyrights, Dear Landlord, The Leftovers, The Dopamines, Be My Doppelganger. I’m sure I’m leaving a bunch of great bands out, but those are the first that come to mind.

D: Would you ever start up a new record label?

L: Probably not. I might be willing to work A&R with an existing label.

D: What current labels are you a fan of?

L: Probably a lot of the ones currently working with the bands I named above. Obviously labels are not quite as crucial as they once were, at least not to me, because pretty much all my music now comes in digital download form. But I have to pay my respect to, for example, Whoa Oh Records, who kept things alive back earlier in the 2000s when it seemed like almost nobody cared, and It’s Alive Records out in California seems to be doing great stuff. Also, a shout-out is in order to my friend Joe Steinhardt’s Don Giovanni Records, which seems like one of the best-run labels around these days, even though, to be perfectly honest, I’m not a huge fan of all the bands they feature.

D: Do you know anything about Lookout’s current state? Will they ever release another album or are they strictly a back catalog?

L: I know they owe a lot of money to a lot of people and don’t seem to be making any progress – or maybe even any attempt – to pay it back. Until they do, it’s hard to imagine them starting to release new records again. It seems like if they did, all their creditors would immediately go after them for a share of the proceeds.

D: You recently did some shows with your old band, the Potatomen. Do you still write songs, and would you record new material with them or other projects?

L: Just the one show so far, though I’d like to do a few more. I really enjoyed it, and it seemed like the crowd did, too. As for writing new songs, well, believe it or not, I’ve been working on the same handful of songs that are almost but not quite finished since the Potatomen stopped playing regularly at the end of the 90s. Seriously; some of them are only missing a few lines out of the lyrics, and I’ve been kicking them around in my head for 10 years or more. However, on the plus side, I’ve lately been playing a lot more guitar and I’ve filled in a few of the blanks. I actually think most of the incomplete songs will be finished this spring and I can finally start on some new ones. Also, we played one song (“Toytown”) at our New York show that had never been released before, and we’ve got a couple others that have not only never been released but have never been played live, though we did demos of them. As soon as someone offers us a show, preferably on the West Coast, especially at Gilman, we’ll be there.

D: As one of the seemingly few people in the their 60s still going to shows, how many people within the punk scene who are now in their teens, 20s, or 30s do you think will stay involved as they reach middle age and beyond?

L: That does seem a little weird when you put it that way, “in their 60s,” but yeah, it’s true. You know, I don’t think it’s fair to measure people’s involvement by a single standard. For example, one reason I’m free to go to a lot of shows, even when it involves traveling some distance, is that I never married or had a family. Obviously things would be different if I had a wife and/or kids waiting at home for me, or if I had some sort of job where I had to be there every day for 50 weeks out of the year. The fact that for the majority of people, that’s what reality looks like doesn’t mean they’ve necessarily lost interest in punk rock music or the punk rock scene, it just means that new priorities have developed in their lives. I don’t think anyone would seriously suggest that a man or woman of any age should neglect their family responsibilities or their personal lives in order to maintain a presence on some nebulous sort of “scene.”

At the same time, I definitely miss seeing many of the people who are no longer able to come out to shows on weeknights or have to visit the in-laws or take the kids to their school play on weekends, but hey, life goes on. Maybe they’ll be back when the kids are grown up, maybe I won’t be around anymore by the time they do. Being part of “the scene” is not like joining the army or a religious cult; it’s something you do because it brings satisfaction and excitement into your life. Most people, given the normal course of events, will eventually find other, non-music-related things that will bring similar or even greater satisfaction and excitement into their lives. But if and when the music is outstanding enough, I expect they’ll still be around. It’s important to remember that they don’t owe their lives to music or “the scene” any more than music or the scene owes any responsibility to them.

D: Something that I’ve noticed about you is that you champion having a sober lifestyle. In some of your writings you describe your earlier lifestyle as seemingly one of heavy psychedelic use, like the piece about going to the original Woodstock Festival. And in Ben Weasel's book, to me he made you out to be a pothead. If it’s not too personal, I was wondering if you could talk about your sobriety and what brought it on.

L: A couple of corrections: first off, I don’t “champion” any sort of lifestyle. Second, I’d like to think of myself as having a life, not a style.

It’s true that I do talk about my experiences with drugs and alcohol, and about the fact that I no longer use either, but not because I’m promoting some kind of program of abstinence for others. My only reasons for talking about this are a) people often ask me questions about my life and seem genuinely curious about it; and b) there’s always the possibility that some of my experiences will be useful to someone who is going through some of the same problems I did.

That being said, I did use a lot of drugs when I was younger, and not just psychedelics or pot, either. It’s worth noting, though, that by the time Ben Weasel met me, I had long since given up psychedelics and all but given up pot. If indeed he was making me out to be a pothead in his book, I’d have to guess it was because he didn’t have that much firsthand experience with real potheads and just assumed that marijuana was the explanation for my seeming a little unusual to him (trust me, there are a lot of reasons why that would be, and one of them was simply that even normal Californians seemed a little weird to people who grew up in the Midwest, and I was definitely not a normal Californian).

In my own case – and this is just speaking for me, not for anyone else – the drugs kind of wore out their welcome on their own, and eventually they were messing up my life more than they were enhancing it, so I gradually quit them – though not without doing a lot of damage first. But with booze it was different: I started out drinking heavily when I was a teenager, tapered off a bit when I discovered drugs, then returned to drinking, and even though by the time I was in my 20s I realized there was nothing particularly cool or desirable about alcohol, I kept on drinking, long after I could see that it was doing serious damage to me.

So I didn’t quit drinking because of some moral crusade or because I thought it was what people “should” do, but because I had to. It was literally killing me. I’m pretty sure that I wouldn’t be alive today if I hadn’t stopped drinking when I did (2001). Now the thing is that among my friends, there are almost certainly people who are having the kinds of problems with alcohol that I was having. But at the same time, there are many people who drink, maybe even get drunk once in a while, but don’t have those problems. Drinking is just something they do now and then, that they can take or leave whenever they want.

The trouble is that I have no way of knowing for sure which is which, which friend desperately needs to stop drinking or else will die, and which friend can go on drinking the rest of his or her life without anything especially bad ever happening.

So I’m in no position to preach or to tell people what they should do. If they want my advice, they can ask for it. Otherwise, I’m just talking about my own experience, strength and hope, and they’re welcome to take from it anything they find useful and to ignore the rest. As I’ve said elsewhere, my life is great now and I’m happy to be a non-drinking, non-drugging writer, musician and occasional punk rocker. I don’t advocate any of that as a life or a lifestyle for anyone else, but it works for me.